| The best known 'character' at Vindolanda

is Flavius Cerialis, prefect of the ninth cohort of Batavians, who

lived with his family in the praetorium at Vindolanda in

the years around AD 100. His correpsondence accounts for over 80

letters of the published and unpublished tablets. We learn little

directly of Cerialis himself, but some things can be guessed of

his likely background. The name Flavius

suggests that he came from a family that gained the citizenship

under Vespasian, perhaps through loyalty to Rome during the Batavian

revolt.

Tablet database link: Browse the correspondence of Cerialis.

The commanders of auxiliary units were required to be of 'equestrian'

rank. This was a high social status that depended on meeting a property

qualification of 400,000 sesterces,

as well as free birth. For some the rank of prefect of an auxiliary

unit might perhaps be the culmination of a military career, for

others greater things beckoned. Brocchus for example, one of Cerialis'

correspondents, probably later commanded a cavalry unit in Pannonia

(Hungary). Other equestrians became senior officers (tribunes) in

a legion.

The governor of Britain is occasionally glimpsed in the tablets.

One letter (248)

implies that Cerialis is soon to meet the governor, in another (225)

Cerialis uses an intermediary to gain access to him. Perhaps a close

personal connection explains the service of troops from Vindolanda

in the governor's bodyguard. The governorship of Britain was a senior

and trusted post because of the size of the garrison, three legions

as well as auxiliary units, a total army of roughly 50,000 men.

The governor had to be of senatorial status, an experienced soldier

and trusted not to use his army to challenge the emperor, a trust

sometimes misplaced.

Tablet database link: Browse the tablets that mention the governor of Britain.

The familia

Click on the image for a larger version.

|

Image

details:

A child's woollen sock, with an upper and

a sole tacked together. Footwear has revealed women and children

as well as soldiers living at Vindolanda.

Image ownership:

© Vindolanda Trust |

The fort prefect was accompanied in his posting by his family,

including his wife and children and the broader familia of

household slaves. The correspondents of Cerialis' wife, Lepidina,

included Claudia Severa, wife of another garrison commander, Aelius

Brocchus, as well as other women (Paterna, Valatta). The reference

to Severa's son in the birthday invitation (291)

reminds us that children lived in the fort as well. Other evidence

for children includes their shoes amongst the leatherwork, and perhaps

the writing exercise (118).

A letter to Cerialis (260)

includes a greeting to the pueri, perhaps Cerialis' slaves.

There are however more certain references to slaves in other officers'

households (301,

347).

Click on the image for a larger version.

|

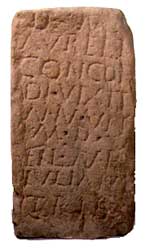

Image

details:

An inscription commemorating Aurelius Concordius

(RIB 1919).

D(is) M(anibus) / Aureli / Concor / di uixit

/ ann(um) un / um d(ies) V / fil(ius) Aurel(i) / Iuliani /

trib(uni)

'To the spirits of the dead (and) of Aurelius

Concordius: he lived 1 year, 5 days, son of Aurelius Iulianus

tribune.'

Image ownership:

© The Museum of Antiquities of the University and

Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne |

Inscriptions from other northern frontier sites reveal the presence

of family members of the garrison commander. The one year old Aurelius

Concordius, infant son of the tribune at Birdoswald, was commemorated

by his father, Aurelius Iulianus. On a long epitaph, Julia Lucilla

commemorated her husband Rufinus, prefect of the garrison at High

Rochester (of the first two lines only isolated letters survive,

but his name is known from another inscription), listing his offices

and honours (RIB 1288).

to … of the First cohort of Vardulli… prefect of the

1st cohort of Lusitanians, also of the 1st cohort of Breuci, sub-curator

of the Flaminian Way and Doles, sub-curator of public works, Julia

Lucilla, of senatorial rank, (set this up) to her well deserving

husband: he lived 48 years, 6 months, 25 days.

Postings to Britain's northern frontier must at times have been

both dangerous and tedious for families, although glimpses

of birthday parties and festivals suggest another side to life.

Tablet database link: Browse the correspondence of Lepidina, or

the tablets that mention slaves or women.

Soldiers

The tablets also refer to many individuals of lower rank,

junior officers, ordinary soldiers, though we learn little more

about them than we can extract from their names and ranks. The names

for example in 180,

recording the dispensation of wheat, include Macrinus, Felicius

Victor, Spectatus, Amabilis, Crescens, Firmus, Candidus and Lucius,

sound Roman. Some of these individuals may be Italian, but the adoption

of Roman names by non-Roman auxiliary soldiers is a well-known phenomenon.

One such individual is Sabinus Trever (182).

Sabinus is a Roman name but Trever indicates his origin in

another northern Gallic tribe, the Treveri, based around Trier (Augusta

Treverorum) in western Germany. As well as other Latin names (Felicio,

Sanctus), 182

also records several Celtic names, including Atrectus, Exomnius

and Andecarus. 310

gives further examples of Celtic names, Veldeius / Veldedeius and

Velbuteius, and two Germanic names, Chrauttius and Thuttena. Some

Greek names are attested, for example Paris and Corinthus (311).

These might be slaves, who often had Greek names. The diverse cultural

connections suggested by the names illustrate the cosmopolitan culture

of the army.

The Vindolanda tablets allow an insight into the close bonds between

individual soldiers, for example letters between 'messmates' (contubernales)

(310,

311).

We otherwise very rarely hear the voices of ordinary Roman soldiers,

save as stock characters in Roman literature. Study of modern armies

suggest that morale is based on the mutual loyalty of soldiers in

individual units. The Vindolanda letters may then echo one of the

features that made the Roman army an effective fighting force, although

references to deserters suggest morale was not always sustained

(226).

Under Roman law, no soldiers below the rank of centurion were entitled

to be legally married until AD 197. Previously marriages were not

officially recognised but were perhaps nevertheless de facto

unions. Marriage is mentioned in one text (277),

but it is not clear to whom it refers. Perhaps women referred to

in some tablets were soldiers' wives (310).

Footwear and jewellery also indicate the presence of women and children

in forts at this period. If they were permanent residents in the

forts, pressure on space in the cramped barrack

blocks would have been unimaginable. Soldiers perhaps also had

slaves, although no certain examples are identified in the tablets.

Traders

In a small number of cases individuals named in the tablets can

be plausibly identified as civilians. Octavius and Candidus (343),

who correspond concerning the transport of grain and animal hides,

as well as other individuals (192,

207,

344)

were probably civilian traders with a contract for supplying the

army. These negotiatores are better documented on the frontier

zone in continental Europe, where they established themselves through

their involvement in the long-distance movement of goods to the

army along the Rhône and Rhine. Vici outside the frontier

forts perhaps housed such traders, as well as families and dependants

of the soldiers, and veterans, but there is no evidence of the existence

of such a settlement at Vindolanda contemporary with the tablets.

It might have been located in one of the unexplored areas, for example

to the north of the Stanegate road. The visible

remains of the civilian settlement at Vindolanda date to a much

later period.

|